Micro-organisms can be friends of future colonists who live elsewhere in the lunar, Mars or solar system and want to establish self-sufficient homes.

Space colonists, like the people of the earth, will need things known as rare earth elements that are important to modern technologies. These 17 elements, with difficult names such as yttrium, lanthanum, neodymium and gadolinium, are rarely distributed in the Earth’s crust. Without the rare earth, we wouldn’t have some of the lasers, metals and powerful magnets used in cellphones and electric cars.

But mining them on Earth today is a difficult process. Tons need to be crushed suddenly and then the fumes of these metals need to be corrected using chemicals that leave behind toxic wastewater streams.

Experiments on the International Space Station show that a potentially cleaner, more efficient method could work on other worlds: let the bacteria do the dirty work of separating the Earth’s rare elements from the rock.

“The idea is that biology is essentially stimulating a reaction that occurs very slowly without biology,” said Charles S. Kokel, professor of astrobiology at the University of Edinburgh.

On Earth, such biomining techniques are already used to produce 10 to 20 percent of the world’s copper and in some gold mines; Scientists have identified microbes that help the earth’s rare earths get out of rocks.

Dr. Kokal and his colleagues wanted to know if these germs would still live and work effectively on Mars, where the Earth’s gravity is only 38 percent of the Earth’s gravity, or even when there is no gravity. So they sent some of them to the International Space Station last year.

As a result, Published in the Journal of Nature Communications on TuesdayShow that at least one of those bacteria, a species called Spingomonas desicabilis, is not affected by forces of varying severity.

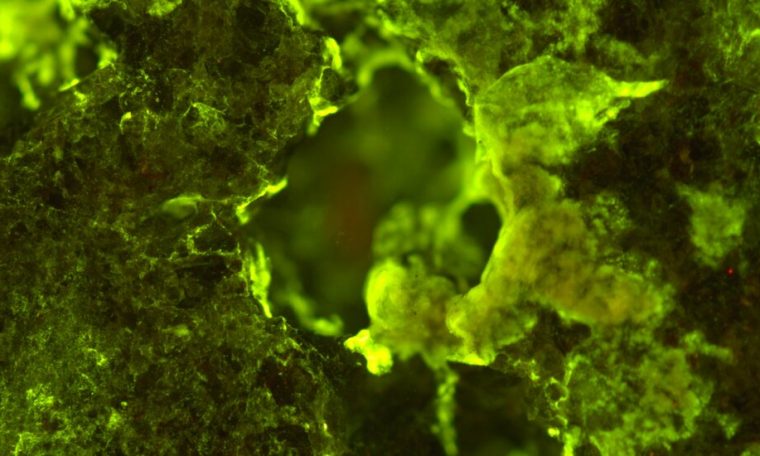

In the experiment, called Biorock, 36 samples were rolled in match box-sized containers with pieces of basalt (common rock made of frozen lava). Half of the sample contains three types of bacteria; The other was just basalt.

On the space station Luca Permitiano, a European space agency astronaut, Placed some of them in a centrifuge at the speed of mimicking the gravity of Mars or Earth. Other specimens experienced the empty-floating environment of space. Additional ground control experiments were performed.

After 21 days, the bacteria disappeared, and the samples returned to Earth for analysis.

For two of the three types of bacteria, the results were disappointing. But S. Discibilis increased the amount of rare earth elements extracted from basalt by a factor of about two, even in zero-gravity environments.

Dr. “It surprised us,” Kokel said, explaining that without seriousness, there is no infection that usually takes the waste out of the bacteria and replenishes the nutrients around the cells.

“Then one can guess that microgravity will stop germs from biomining or it will force them to insist that they were not biomining,” he said. “Actually, we weren’t affected.”

The results were somewhat better for the lower part of Mars Gravity.

Pym Rasulnia, a doctoral student at the University of Tampere, Finland, who studied biomining Of very little earth elementHe found the results of the biorock experiment interesting, but noted that the yield was “very low even in ground experiments.”

Dr. Kokal said the biorock was not designed to be accurate. “We’re really looking at the basic process that characterizes biomining,” he said. “But it’s certainly not a demonstration of commercial biomining.”

The next SpaceX cargo mission to the space station, which is currently scheduled for December, will be followed by a biostroid name. Instead of basalt, matchbox-sized containers will contain meteorite and fungus fragments. They, instead of bacteria, will be the agents they test to break the rock.

Dr. “I think, after all, you can be massive enough to do that on Mars,” Kokal said.